I. Indigenous Architecture: “Local Wisdom” in Harmony with Nature

As the origin of Australian architecture, Indigenous buildings rely entirely on natural local resources, adhering to the principle of “minimal intervention” to adapt to extreme climates. They represent early examples of place-based design. Aboriginal people traditionally built no permanent structures; instead, they created temporary, portable shelters that changed with migration routes and seasonal shifts. The core purpose was to withstand the continent’s heat, strong winds, and heavy rain.

The most representative forms are the “Wurley” and “Gunyah.” The Wurley, common in southeastern Australia, uses eucalyptus trunks as frames and is covered with bark, grass, or branches to form a low dome shape. This design reduces direct sunlight and blocks cold winter winds through tightly layered coverings. The Gunyah, popular in the tropical north, features a taller frame with ventilation gaps and palm-leaf roofs that allow hot, humid air to escape quickly, preventing stuffiness indoors.

Some coastal tribes built simple shell or stone walls to resist sea winds and tides, while desert shelters were often set into rock hollows to take advantage of natural insulation. Though simple in form, these buildings reveal a precise understanding of the climate—low shapes for wind resistance in arid areas, open structures for tropical airflow, and low-conductivity natural materials (like bark and grass) to maintain interior stability. This philosophy of “working with nature” later became a major inspiration for Australia’s modern architecture.

II. Colonial Architecture: Style Adaptation and Climate Response

After European colonization in the late 18th century, Western styles entered Australia. However, they were not copied directly but climatically adapted, combining colonial aesthetics with local functionality.

- Victorian Style (Mid to Late 19th Century)

Originally from Britain, the Victorian style in Australia underwent significant “lightweight” modifications. British Victorian buildings featured heavy masonry walls, steep roofs, and ornate carvings suited to a temperate maritime climate. In Australia, builders replaced stone with local timber (like pine) to reduce both weight and heat conduction. The tall rooflines were retained for better drainage during summer storms, but lighter terracotta tiles replaced thick stone slates.

Windows were enlarged into bay or floor-to-ceiling designs to improve ventilation and admit winter sunlight—important in the cooler southern regions. Open verandas (verandahs) became a defining feature: the shaded roofs blocked harsh summer sun, while the space below acted as a semi-outdoor “transition zone” for family and social activities.

- Queenslander Houses (“Stilt Houses”)

This is the most regionally distinctive colonial style, designed specifically for the tropical and subtropical climates of northeastern Australia—and still an icon of Queensland today. The “Queenslander” is a textbook response to local weather challenges: high heat, humidity, heavy rainfall, and cyclones.

Key features include:

Raised floors: The building stands 1–2 meters above ground on timber stilts to prevent flooding and improve air circulation underneath, reducing indoor humidity and temperature.

Open structures: Walls are made of removable wooden panels or louvered shutters that can be fully opened in summer to create cross ventilation and closed in winter to block cold winds.

Wide eaves and wraparound verandas: The extended roof shades the walls and outdoor spaces, reducing heat gain and providing functional outdoor areas for drying clothes or relaxing.

Lightweight materials: Primarily wood—resilient to wind, low in thermal conductivity, and capable of withstanding cyclones while keeping interiors cool.

The “stilt house” is a near-perfect response to tropical climates and remains a key reference for modern residential design in the region.

III. Modern and Contemporary Architecture: Eco-Oriented and Sustainable

From the mid-20th century onward, Australian architecture gradually broke free from traditional stylistic constraints, shifting toward modern designs that integrate functionality and ecology. With the rise of global environmental awareness, sustainability became the central theme, giving rise to several adaptive architectural trends.

- Modernist “Prairie-Style” Derivatives

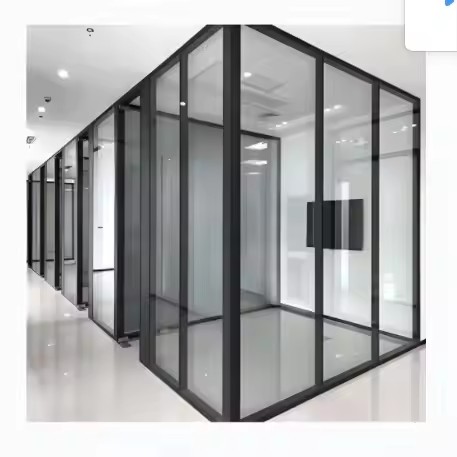

Influenced by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, modern Australian architecture emphasizes integration with the landscape, often using horizontally oriented forms that harmonize with Australia’s open plains and coastal terrain. Buildings typically extend along the ground rather than stacking vertically, minimizing terrain disturbance. Roofs are flat or gently sloped, with large glass curtain walls that maximize daylight while maintaining thermal efficiency.

Indoor and outdoor spaces flow seamlessly—sliding glass walls connect interiors with gardens, pools, or patios, encouraging direct interaction with nature. This style is especially popular in suburban Melbourne and Sydney, fitting the temperate climate and Australians’ love for outdoor living.

The modernist aesthetic—clean, simple, and functional—remains widely favored for its alignment with contemporary tastes.

- Eco-Sustainable Architecture

Facing increasing environmental challenges such as drought, heatwaves, and bushfires, Australia has embraced eco-architecture focusing on low energy use, low emissions, and high adaptability. Design strategies are deeply climate- and resource-driven.

For example, commercial and residential developments are planned with site-specific environmental strategies—using renewable materials, passive ventilation, solar energy systems, and rainwater collection. In housing developments, eco-friendly designs not only meet sustainability goals but also align with modern buyers’ growing preference for green living.

Such sustainable approaches now define the direction of contemporary Australian architecture, balancing aesthetics, comfort, and environmental responsibility.